HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

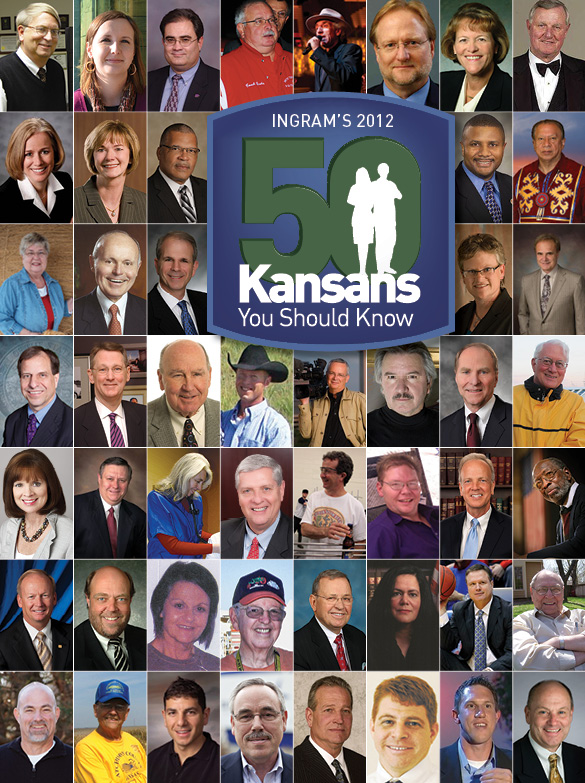

Since the inaugural production of our 50 Kansans You Should Know feature in 2011, the editors and researchers at Ingram’s have had the opportunity to consider more than one thousand deserving residents of the Sunflower State.

Unlike other business-recognition honors that are often based on demonstrated, superior performance within a given business sector, we’re looking for something different: accomplished individuals who weren’t necessarily the CEOs of the biggest companies, or the fastest-rising stars of C-level execs. Our goal was to capture not just a sense of what business leadership has to offer, but other figures, some iconic, some flying under the radar, whose achievements have added depth and texture to life in Kansas. We also have pursued the selection of characters with character.

Without being too boastful, we like to think we succeeded beyond our most fervent hopes. When you look past a resume and ask people to talk about the core values of the state—and how those values inform their professional lives and personal views—the steady recitation of certain traits begins to form something like a mantra, one you won’t hear repeated quite the same way in other locales.

Gen. Deborah Rose, who has since retired from her position in the Kansas Adjutant General’s office, touched on an oft-repeated theme last year: “I love Kansas; I wouldn’t live anywhere else. It’s the people of Kansas, the Midwestern hospitality,” she said.

But she also saw something more, something that goes to the heart of what makes Kansas a great place to do business or raise a family: “The collaborative thinking that we have in Kansas,” Rose said, was a defining characteristic of the state. We heard that over and over not just last year, but with the 2012 version of 50 Kansans You Know. “I firmly believe that we are the most collaborative state in the nation,” Rose told us. “We do things not for someone to receive credit; we couldn’t care less about the credit—we just we want our state to be the best.”

Something else we learned: Kansas has highly accomplished individuals almost anywhere you turn. Of the 100 people recognized so far, we’ve been able to spotlight people from nearly 20 sectors. Among them are public officials, retailing and restaurant operations, manufacturing, energy, technology, transportation, hospitality, communication—they literally come from every walk of life.

And not just from the major metropolitan areas of Kansas City, Wichita or Topeka, either: nearly half those recognized to date come from smaller communities, ranging from tiny burgs like Cawker City and Horton to college towns like Lawrence, Manhattan and Pittsburg.

How do people achieve so much across such a great expanse? Maybe the best explanation for that was offered by Wichita’s Jill Docking, who suggested that the state’s social structure had unlimited opportunity hard-coded into it: “I think what’s unique about being a Kansan,” she said, “is that it’s a state small enough that individuals can really have a significant impact” in their respective communities.

Opportunity, then, combined with the right values, gets you here: To 50 Kansans You Should Know.

Bob Page

University of Kansas Hospital Kansas City, Kan.

“There is no arrogance surrounding the solid accomplishments of the Kansas people,” says Bob Page. “They do things right because that’s the way things are supposed to be accomplished.”

That core value of humility, yoked to an inherent commitment to competence, produces comebacks from natural disasters like Greensburg post-tornado, or economic disasters, like Wyandotte County was a decade ago, Page says.

He’s seen the power of both at work at the University of Kansas Hospital, from the time he started in 1996 through his rise in the administrative ranks to chief oper-ating officer before being named president and CEO in 2007.

Over that span, he has been integral to the hospitals efforts to change its administrative structure to the current model as a public health authority, he’s drawn on his accounting and business skills to boost operating margins, and he’s managed or overseen more than $355 million in capital improvements projects. That has paid off in soaring levels of patient admissions, making it by far the market leader in that category.

The personal rewards of all that, he says, come from the patients. “We are encouraged when patients travel to M.D. Anderson (the Texas cancer hospital) or the Mayo Clinic, only to be told the best place to get care for their problem is right here in Kansas,” Page says.

The distinguishing feature of that care, he says, is the unmatched kindness and commitment he sees from members of the hospital team. Witness the staffer who made a round trip of more than three hours to Emporia, 105 miles distant, just because a patient said she couldn’t find another ride home.

“I am so honored to work with the extraordinary caregivers in this organization,” Page says.

Jeffrey Turner

Spirit AeroSytems, Wichita

The leader of the world’s largest independent supplier of commercial airplane assemblies and components—Spirit AeroSystems—Jeffrey Turner has spent nearly four decades working his way up the rungs of success in the Air Capital of the World.

Turner spent more than 30 years with the Boeing Company, starting 1n 1973 as a part-time programmer while he was in still in college at Wichita State University. The Kansas native was named president and CEO in June 2005, when Boeing’s Wichita division was acquired by Onex and renamed Spirit AeroSystems.

Before Spirit AeroSystems, Turner held a number of management and director positions with Boeing Computer Services, Boeing Military Airplane Co. and Boeing Commercial Airplanes. Turner earned his bachelor of science in mathematics and computer science, as well as his master’s in engineering science, at Wichita State University. He was chosen as a Boeing Sloan Fellow at the Massachusetts Institute for Technology’s Sloan School of Management, where he received his master’s degree in management.

Jack Dicus

Capitol Federal Financial, Topeka

Topeka is just an hour removed from Kansas City, but when you think of a family banking dynasty there, the first name you’re likely to hear from the locals isn’t Kemper—it’s Dicus. As in John C. Dicus— better known as Jack—the patriach of the family that has long controlled what is now Capitol Federal Financial. For nearly half a century, he helped build Capitol Federal into one of the region’s biggest financial institutions.

In 2009, he turned the reins over to his son, John B., in 2009, making him chairman, president and CEO. Jack Dicus retains the title of chairman emeritus of a bank with nearly $8.5 billion in assets, making it the third-largest locally owned bank in the greater Kansas City region.

As things turned out, Jack made the right call by going to work for his father-in-law, Cap Fed president Henry Bubb, not long after graduating from the University of Kansas in the mid-1950s. The bank has contributed much to Topeka’s economic vibrancy over the decades, and because of Dicus’ vision, it has made a similar impact on the city’s philanthropic endeavors. He was largely responsible for the bank’s establishment of its own philanthropic division—The Capitol Federal Foundation, committed to improving the quality of life in cities where it operates.

The millions of dollars that have flowed from the foundation still benefit the city today. The city, in turn, paid tribute to Dicus in 2006, naming him to the Topeka Business Hall of Fame.

Elizabeth King

Wichita State University, Wichita

Kansans are humble, selfless, have a deep sense of community; and, because of a strong personal work ethic, their word is their bond, says Wichita State University Foundation President and CEO Elizabeth King.

King, who essentially has reconditioned WSU’s fundraising program, helped increase the foundation’s assets since joining from $53.8 million

to about $225 million and has grown the annual amount raised from $7 million to more than $27 million, on average. A significant challenge King and her staff

have faced in their efforts, however, has been the economic instability of the past several years.

“The most difficult part of fundraising during an economic downturn is the realization that many deserving students and programs will not receive the level of financial assistance we seek to provide,” she says. “The foundation has grown in market value of assets from $54 million to well over $200 million, yet our students’ needs for support have also dramatically increased.”

A testament to King’s dedication and enterprise, she has received numerous accolades for her work, including receiving the Wichita State University Alumni Association’s Recognition Award in 2006 and being named 2009 recipient of the CASE Commonfund Institutionally Related Foundation Award for her contributions and longtime support of the foundation and overall profession.

King has been in her position for more than 20 years; numbers and statistics aside, she says the most rewarding aspect of her job has been “building relationships with

donors and then facilitating their vision to enhance our university.”

Linda Brantner

Delta Dental of Kansas, Wichita

Linda Brantner, president and CEO of the largest and oldest dental benefits carrier in the state, is proud to be a Kansan. She believes in hard work and not being afraid of new challenges, and draws on two Kansans historical figures for inspiration: Amelia Earhart and Gordon Parks. “Earhart was an adventurer who defied conventional feminine behavior to follow her passion of flying,” she says. “Her courage, brave spirit and groundbreaking achievements for women are an inspiration.” Parks, Brantner says, was a survivor—a self-taught artist and an icon. “He overcame unimaginable childhood barriers to become an acclaimed photographer, writer and filmmaker.”

With a strong connection to her home state, Brantner finds time to devote to her local Wichita community, where she also serves on the boards of various civic, philanthropic and not-for-profit organizations.

Her appreciation for Kansas goes deeper than the cities, people and organizations situated within state lines; she draws on the Flint Hills for reflection and as a way to connect with the land. “Since my work takes me back and forth from Wichita to Kansas City quite often, I love the peace and serenity of the Flint Hills,” she says. “During those drives, I turn off my cell phone and take a couple of hours to enjoy the landscape.”

Fred Logan, Jr.

lawyer, Leawood

Family, says lawyer Fred Logan, comes first—always. Then his clients. “Every remaining waking hour,” he says, “can be put to use to advance the right causes.”

Logan must not sleep, because if you count the number of causes he considers right, the math implies a 37-hour day. A passionate believer in the power of education to generate economic growth, he’s been an advocate at every level. He currently sits on the Kansas Board of Regents, setting policy for the state’s public universities and community colleges, and has been chairman of the board of trustees for Johnson County Community College. K-12 education has held his attention as well; he’s a past winner of the Shawnee Mission Education Foundation’s Patron Award for distinguished service to the district and to public education.

“I believe that Kansas can become great through its institutions of higher education,” Logan says. “It’s no coincidence that the state’s two most important initiatives—NBAF, in which K-State plays a key role, and KU’s campaign to win National Cancer Institute designation for its cancer center—are higher-education initiatives. That is why I love serving on the Board of Regents.”

Higher education, he says, is the launch pad for efforts to modernize a state economy long grounded in manufacturing and agriculture. “Life sciences represent the greatest opportunity to advance the Kansas City region,” he says. “In just a decade, we have created important assets in animal health, cancer and

medical research, and drug innovation.”

His inspiration for getting things done comes, in part, from the example set by former Sen. Bob Dole, whom he calls “the quintessential Kansan.” “He got it done in so many ways. I was privileged when I was state Republican chair in the late ’80s to fly around the state with him for three days. Quite an education—and an honor.”

Joseph Galichia

Galichia Media Group, Wichita

Wichita is famed for pioneering entrepreneurs: The Koch family, the Carney brothers and names like Beech, Cessna and Lear. Here’s another one: Joseph Galichia. He’s a cardiologist who revolutionized coronary care in the 1980s by introducing balloon angioplasty to the United States after studying under its inventors in Switzerland. Far less invasive than traditional heart surgery, the technique uses a catheter, inserted into the femoral artery, to treat heart and vascular conditions.

Galichia helped popularize it by building the world’s first freestanding outpatient catheterization laboratory. He followed that up in 1984 by launching Galichia Medical Group, which earned acclaim as one of the world’s leading centers of innovation in the treatment of vascular disease. Still not done, he founded Galichia Heart Hospital in 2001, where patient care is backed by research in carotid stenting, robotic surgery and other innovations.

Roy Applequist

Great Plains Manufacturing, Salina

Roy Applequist launched Great Plains Man-ufacturing on April Fool’s Day 1976, but he wasn’t fooling around: Driven by an idea for a better grain drill and infused with a work ethic that runs four generations deep, Applequist would build his company into a true powerhouse in the farming equipment sector. Great Plains operates not only throughout the 48 lower states, but has a reach that extends all the way to Great Britain; roughly 100 employees at its factory who supplement the output of seven Kansas-based production facilities.

He made the leap into business ownership after his previous employer—his father—retired and sold his company that made components for the agricultural sector. All of 30 years old at the time, Roy recalls, “I could tell pretty quickly that I wasn’t wanting to work for a big international company. I wanted to do my own thing.”

That he has: Great Plains now employs more than 1,225 people across Kansas, serving as anchor industries in most of the towns where it has a presence, and is a major employer in Salina. That’s not far from the farm Applequist’s great-grandparents homesteaded in the 19th century when they joined like-minded Swedes pouring into the area around Lindsborg.

Applequist’s connection to the land runs deep. “There’s a pretty strong sense of community, in this state,” he says, “especially in smaller cities and towns. Out here, loyalty to the people you work with is really important.”

Dennis Langley

Management Resources Group, Lenexa

Dennis Langley remembers his dying father’s last words to him: “Don’t ever forget where you came from.” That counsel serves as a guidepost for Langley’s work in both “old” energy—natural gas—and newer alternative, environmentally friendly forms. He owns Lenexa-based Management Resources Group, which provides consulting services in sustainability to corporate clients. The 1999 sale of Kansas Pipeline Co. generated capital for various alternative-fuels ventures, and though those haven’t proven as successful—yet—Langley’s commitment to them speaks volumes about what his dad taught him: “You have to be willing to fight for what you believe in, and have persistence,” says Langley. “Most people give up when they have a setback; you’ve got to stay with it.” Langley said his views, and his longtime leadership role in the Democratic Party at both state and national levels, didn’t always square with the values of others in the energy field. “Sometimes it helped, sometimes it hurt me,” he said, but he’s resolute in his belief that energy policies advocated by his party are essential to long-term economic viability.

Frank Friedman

Deloitte, Leawood

Kansas values are one thing. The value of Kansas is another. For Frank Friedman, the latter was paramount, even when the global accounting firm Deloitte anointed him its chief financial officer. Friedman would take the job—but insisted that he would remain in Kansas City. “I was born in Kansas City, grew up in Kansas City, went to the University of Kansas and started work in Kansas City,” Friedman says, mentally retracing his path.

“Today, I go to New York a lot or travel someplace every single week. It’s nice to be in New York; there’s a sense of excitement.” But coming back home is exciting, as well, he says, in part because “there are no false pretenses” here.

His experience says a lot about what defines this part of America. It also says something about the changing nature of business in the digital age. “I know we can do our job from any place in the country; it’s not necessary that you pick up your whole family and move” with all the attendant stresses. “If you can still be successful and do the job,” he says, “it shouldn’t matter where you do it from.”

On his rise to the C-suite, Friedman’s duties as managing partner frequently took him out into the state, to the larger cities of Topeka and Wichita, or smaller communities like Manhattan and Coffeyville. “I love going out there,” he says, “but for me, my retreat actually is, from time to time, Allen Fieldhouse,” back on the campus of his alma mater. “That’s the best time for a Kansas Jayhawk, and about as exciting a place as you can imagine. For me, I love sports and KU basketball. It just gives me a chill to be there.”

Carl Brewer

Mayor, Wichita

“As a native Kansan, I have learned there is no substitute for hard work,” says Wichita Mayor Carl Brewer. Wichita’s first elected African-American mayor has a career background in aviation, including companies such as Cessna, Boeing and Spirit AeroSystems.

Throughout his experiences in both business and government, he says he has found some common ground between the two. “In both sectors, there is a need to clearly identify the goal and mobilize your constituency to address the challenge. You have to build consensus across all demographic boundaries and you have to learn to appreciate that all opinions are important.”

Prompted to run for mayor by “the challenges that were before us,” he says, “I hoped that I could help create a constructive dialog that would unite our community behind a common economic development agenda.” Brewer says he strives to maintain the quality of life that makes “Wichita one of the best places in the country to raise a family.” This has meant competing with other cities and states to preserve the city’s economic base.

With Brewer’s deep connection to the state, he looks to several other Kansans for inspiration. “Our state has generated a wealth of business and political leadership, ranging from Clyde Cessna to the founders of Pizza Hut,” he says.

Mary Birch

Lathrop & Gage, Overland Park

Kansans, says Mary Birch, are resilient, pragmatic, slow to change and loyal to a fault. And Birch should know, because she’s had the opportunity to work with so many of them. For 18 years, she served as president of the Overland Park Chamber of Commerce, and today she’s the government relations coordinator for the Lathrop & Gage law firm in Kansas City.

Her experience in those roles and her vast connections give Birch unusual influence in state policy circles. Just one example: She and Dick Bond (you’ll read about him elsewhere in this feature) were key instigators of what would become the Johnson County Education and Research Triangle initiative approved by voters in 2008. Birch helped recruit support to get the measure in front of voters, whose approval of a special sales tax gave birth to the consortium fostering university programming and business development in the life-sciences sector. It was a venture that literally changed the business climate of the Kansas City region.

Typically, Birch deflects credit for that. “The Triangle could not have happened had this community not had a long tradition of supporting excellence in education,” she says. “Johnson Countians strongly support the marriage of quality education to economic development and jobs.”

It also showed a willingness by residents to take the calculated risk and invest in the future, she said.

But the people she’s worked with who make such things happen, she says, are not faceless cogs in a network: “For me, they are relationships. Wonderful humans who have graced my life’s journey and who want to accomplish good things to move lives forward. People who care about Kansas and Kansans, people who want to build community.”

Brandon Steven

Brandon Steven Motors, Wichita

As Brandon Steven sees it, Kansans seem to work harder than most, which he says is a big reason of why it has so many family-owned businesses. With a background in business ownership and entrepreneurship, hard work is in his genes. “I remember being 7 years old, going to my dad’s car wash to help him clean up,” Steven said. “We have worked as a family since I can remember.” In addition to Brandon Steven Motors, Steven owns (or has a stake in) nine Genesis Health Clubs throughout Kansas, Steven Enterprises LLC, two self-service car washes, Rock Road Car Wash & Quick Lube, O’Naturals Restaurant, Enterprise Advertising and Steven Snow Removal. Add into the mix: Steven and his brother, Rodney, also co-own the Wichita Thunder hockey team (through Steven Brothers Sports Management).

“My brother and I became partners when I was 11 and he was 12” when they embarked on Steven Snow Removal, Steven says, “and we have been partners ever since. We are always trying to outwork each other.”

When he isn’t juggling his businesses, spending time with his family or cheering on a Thunder game [he hasn’t missed a game yet, watching live or via Internet], he can be found working on his poker skills. He has played in five World Series of Poker events and netted $894,650 in lifetime winnings. “Poker has taught me to slow

down a bit in business,” he says. “In poker, he says, “only timed aggression is profitable, and I have applied that to my teams at work.”

Jerry Moran

U.S. Senate, Plainville

Jerry Moran knows what’s needed in the nation’s capital—a hearty dose of Kansas values. “Washington,” he says, “lacks common sense.”

That’s the kind of plain talk you might expect from someone whose hometown was, yes, Plainville. “I think our pioneer history, the settlers, the immigrants, who came to Kansas and had to fight for survival; that continues to affect the nature of Kansans today,” he says. He grew up in a typical Kansas family; “my dad worked in the oil fields and I was raised in a way that hard work is an important attribute, and one that would be rewarded.” The sparse population implied an obligation to take care of friends and neighbors, he said, which fostered a Kansas brand of care, compassion and commitment to community.

After eight years in the state Senate and 12 in the U.S. House, he won the U.S. Senate seat in 2010. In two months leading up to New Year’s Eve, Moran visited every one of the state’s 105 counties for town hall meetings, giving him a keen appreciation for Kansas and its residents. “In lots of communities, I just get out of my car, go walk Main Street and simply visit with folks,” he says. “Just having conversations with typical Kansans is an important way to stay connected with Kansas.”

Bill Self

University of Kansas, Lawrence

He’s an Oklahoma native who played college basketball there and coached two college teams there before landing in Lawrence eight seasons ago.

So when, exactly, did Bill Self become a Kansan? Doesn’t matter; to Self, the question is purely academic: “We can positively say Lawrence, Kansas, is our home,” he declares. “I consider myself a Kansan but I will also always consider myself an Oklahoman.” That settles that. The college basketball world was abuzz with speculation that Self would return to his alma mater, Okla-homa State, four years ago, when he was trying to concentrate on other elements of his to-do list, such as, oh, winning the 2008 NCAA Tournament championship. But he didn’t go—much to the delight of Jayhawk basketball fans. For seven straight seasons, Self has guided KU to at least a share of the conference title. Coaching in a house hallowed for its ties to basketball’s roots, Self says one Kansan he considered inspirational was the late Phog Allen. “He would be one of the people I would have loved the opportunity to sit down and visit with,” Self said. If they could, Self would have brag-ging rights: Allen may have had 590 career victories at KU, but his .790 winning percentage in his first eight seasons there trails Self’s mark of .837.

Dean Oskvig

Black & Veatch, Overland Park

When Dean Oskvig cites Dwight Eisenhower as an example of an inspirational Kansas figure, he does so with the calculating eye of an engineer. Oskvig is president and CEO of the global energy business for Black & Veatch, the 14th-largest design and engineering firm in the U.S. Ike, he said, “orchestrated one of the most logistically complex undertakings in history that preserved a free Europe, and probably the United States” with the Allied invasion of Normandy in 1944. “And he gave credit to others.” That last part says as much about Kansans in general, Oskvig believes: “I think the characteristics of a Kansan are marked by self-reliance, perseverance, and doing what you said you were going to do”—all part of Eisenhower’s playbook, too.

For this native Iowan who has lived more than half his life in Kansas, these are values he brings to work every day. Black & Veatch, he says, champions integrity, accountability, shared ownership and entrepreneurship. “If my own values don’t, or didn’t line up with those, then I wouldn’t have been successful here,” Oskvig says. He also puts those to work with two personal causes: the Blue Valley Educational Association and Children’s International. Both, he said, provide “the satisfaction of knowing what they do makes a difference in people’s lives.” In both, he sees “passion for the people served, and operational excellence.”

Bob Staley

corn-shucking champion, Atchison

Bob Staley blew past retirement age decades ago, and isn’t looking back.

“I’m a fitness freak, to a degree,” the 91-year-old Atchison resident says in a voice that rings with the clarity of a middle-ager. That may be putting it mildly. He sold his loan company at age 65, then took up biking and tackled a 574-mile competitive ride across Iowa before making a name for himself by diving into competitive corn-shucking after he turned 71. He won the national shucking championship for the 75-and-up age group when he was 85, and has finished runner-up twice since then, successes that landed him a spot on “The Today Show” with Matt Lauer. The key to successful shucking? “Technique,” Staley says.

“You have to get the ear out quickly and get rid of it quickly.” Still working today, in antique auctions and in bail bonds, he relishes the annual getaway to Spain with his wife—this year’s trip is No. 35—and he’s a walking museum for Orphan Train lore, an interest fueled by his mother’s experience with that 19th-century social experiment. Staley has slowed a tad, but still gets plenty of activity tending a pair of gardens and 20 fruit trees in his two-acre yard, and he also teaches country-western ballroom dancing. But he had to give up on the biking: “I am getting old, I can tell,” Staley cracks.

Lafayette Norwood

Johnson County Community College, Overland Park

Before the gaudy winning percentage coaching the Johnson County Community College golf team—nearly 70 percent over the past 19 years—before their 14 straight NJCAA tournament appearances, before the Jayhawk Conference titles, Lafayette Norwood had already made history—in another sport. This Oklahoman by birth, along with the late, legendary Ralph Miller, is one of only two Kansans to have ever played on a high-school state championship team (Wichita East, 1951) and coached one to a title. His 1976-1977 Wichita Heights team, featuring five future Division I collegiate starters, closed out an undefeated season with an astonishing 40-point victory over traditional powerhouse Wyandotte High. He was an assistant coach at KU, then got back into the head role at JCCC for 10 years before moving over to golf. Norwood’s pride, though, isn’t tied up in titles. From that Heights team in ’77, he notes, “only three players failed to get their college degree,” and he’s most proud of having taught at every level—primary school, high school, four-year college and now JCCC, which he says has been “a rare opportunity for me.”

Stan Herd

environmental artist, Lawrence

“From an early age,” says Stan Herd, “I had a very strong feeling that my life was going to be a great adventure. I have not been disappointed.” As a boy, he marveled Michelangelo and Van Gogh, and was inspired to pursue art. And he has, quite literally, carved out an international reputation working with the most unusual artistic media imaginable: the typical grain plants of the Midwest. As an environmental artist, Herd specializes in large-scale “sculpture” from fields of wheat, corn, soybeans—even alfalfa. More recently, he has embraced permanent designs using native stone from Kansas quarries, yielding such works as Prairiehenge on the Red Buffalo Ranch near Sedan, Kan. And last month, he was commissioned to create a petroglyph on the campus of Johnson County Community College. His work is infused with values imbued from childhood. “My earthworks grew philosophically from a desire to reconnect with the agriculture, with the agrarian culture that defined this nation,” he says. After leaving his native southwest Kansas, “I began to understand that our family farm experience was part of a disappearing way of life and that my work would become a tribute to that experience and the people who work the land.” Herd also finds inspiration in “the pioneering women of Kansas” too often left in the shadows of important men. “Nancy Kassebaum, my friend Kathleen Sebelius, and my incredible mother Dolores, whose guidance and heart set the path for me and all of my siblings, all remind me of what we Kansans are all about.”

Dick Bond

lawyer, Overland Park

In Dick Bond’s view, moderation isn’t a dirty word—it’s a means of simply getting things done. It’s a quality he brought to the Kansas Senate for 14 years from 1987-2000, including stints as president of that body, and that’s what he brought to the Kansas Board of Regents, where he served as chairman in 2004. It has marked his service as co-chair with noted Democrat Jill Docking for the Kansas Children’s Campaign, and his involvement with Johnson Countians for Education. Belying the notion that Republicans can’t get behind tax increases, he was a prime mover in securing voter approval for the 1/8th-cent sales tax that funded the Johnson County Education and Research Triangle initiative to nurture a fledgling life-sciences sector in the Kansas City region. There was a time in Kansas politics, Bond says, where legislators could “fight like hell but afterwards go out and have a beer together—that’s not the legislative climate today at the state or federal level; civility is gone.” Whether that’s due to the Statehouse’s declining numbers of lawyers—people trained in the skills of gentlemanly point-counterpoint—or rooted in other factors, he says, “there is a lot of hate today in the political arena that I would hope more lawyers would cause that to be diminished. But it’s dangerous and disheartening, and it doesn’t lead to good government.”

Sharon Lee

Southwest Boulevard Family Health Clinic Kansas City, Kan.

In 1989, Sharon Lee put her medical skills and her compassion to work by launching the Southwest Boulevard Family Health Clinic in Wyandotte County. Nearly a quarter-century later, and after a round of raises, she earns all of $14 an hour for her time there. So when people talk about the high cost of health care, rest assured that she’s not part of the problem. Still, being part of the solution gives her pause to reassess what she sees as the shared Kansas values of personal integrity, equality, and diligence. “Individual Kansans are willing to give, sometimes generously, to individuals in need,” she says. “But there is an apparent disconnect when they go to the polls and vote to reduce funding and other supports for the poor. It is hard for true ‘compassionate conservatism’ to play out in government.” Whether it’s helping a patient regain health and get a better job, she says, or helping a mother learn to read and teach her own children, or even helping someone with a terminal illness simply die in comfort, “it is extremely rewarding to do this work. The people we help often get back up, dust off and go on with their lives to do extraordinary things.” Providing inspiration for her work, she says, are my parents. “My mother survived meningitis in the 1930s, at a time when few did; she never quits,” Lee says. “My father also persevered to earn a pilot’s license and got his hours to become a commercial pilot by flying a nightly mail run after putting in a long day at a service station. Both, she said, “have true grit.”

Larry Hatteberg

KAKE-TV, Wichita

No joke: Larry Hatteberg once inter-viewed a man who’d been living in a hole in the ground for the 40 years since his house had burned down. That fellow was old, he was dirty and he had next to nothing, but he taught Hatteberg something no one else ever did in decades of interviewing the state’s rich and poor alike for KAKE-TV in Wichita.

That subject “was perhaps the happiest and most content man I had ever met,” Hatteberg recalls. The old man castigated the reporter for letting day-to-day duties blind him to life’s simpler pleasures. “To this day, when I watch either a sunrise or sunset, I see [his] face as clear as if he were standing in front of me. Sometimes it takes a man who lives in a hole in the ground to make the rest of us see ‘life.’ ”

It’s almost impossible to calculate the number of Kansans Hatteberg has interviewed in 48 award-winning years with the station, especially with segments called “Hatteberg’s People,” featuring subjects who give the state its unique flavor. In many ways, he says, his subjects, like that old man in the hole, “are teachers of ‘life.’ ”

His keen eye for content draws on lessons learned from his father, a baker in Winfield who went out of his way to feed people he’d found rifling through the bakery’s trash bins. “He couldn’t stand to see others go hungry,” Hatteberg recalls. “He never sought publicity for his good deeds and would have been embarrassed if they were pointed out. But he set an example for me that lives on to this day … and one that I know comes through in my work.”

Hank Herrmann

Waddell & Reed, Overland Park

His first 27 years defined him as a New Yorker. What he found after that made Hank Herrmann a Kansan. And not just any Kansan; he’s the CEO at Waddell & Reed, one of the largest wealth-management companies in the Midwest. “What makes me a Kansan is the tremendous sense of core values found here,” Herrmann says. “The living environment we found here was a delightful change of scenery for me and my family.” More than that, though, he saw something special in the people here. “Running a place like Waddell & Reed, what I see in the people that work with us is a real sense of loyalty and commitment to the firm.” That’s a far cry, he says, from what one sees in New York. During his tenure, that has paid off with corporate growth nearly three times the rate of inflation, pushing Waddell & Reed into billion-dollar revenue status last year.

That success, though, hasn’t severed him from what he loves about the state. As New Year’s Eve bore down, he was an hour south of Kansas City, out hunting—his real soft spot, he says. “The Flint Hills is a very special place; I think it’s spectacular country,” he says. “But what I really love is the camaraderie and the experience of going out early in the morning, finding a place to have coffee, bacon and eggs, and just connecting with the people here.”

Jessica Frye

Adjutant General’s office, Topeka

“As a whole,” says Jessica Frye, “Kansans are just as diverse as our landscape.”

And Frye knows a thing or two about landscapes. She’s the GIS coordinator for geospatial mapping technologies in the office of the Kansas Adjutant General in Topeka. That means she’s intimately involved in gathering detailed information that can be critically important after a natural disaster—pinpointed locations for health-care facilities, schools, emergency responders, and even zoos and livestock concentrations.

Despite the growing popularity of GPS systems, hers is a job not many people can relate to, but “being a geographic information system professional brings new challenges and learning experiences every day,” Frye says, “especially when you work for an agency that manages disasters statewide.”

Her role provides endless opportunities to explore the state and learn about it in-depth, she says and her travels have given her perspective of ownership for every map and data set she creates. They also have given her a window to hidden gems of life in Kansas.

“One location that really brings Kansas home,” she says, “is the view from the Chase County Courthouse. Looking out the window on the upper floor and seeing the rolling hills and valleys of the Flint Hills leaves you awe-struck.”

Scott Weir

KU Cancer Center, Kansas City, Kan.

Mission Hills isn’t exactly part of the High Plains, but it is in Kansas, and one of its most famous residents, the late Ewing Kauffman, planted a Sunflower Stamp square on the forehead of Scott Weir 26 years ago, when Weir joined Marion Labs. The young native of Nebraska was taken aback by the level of adulation he witnessed for his new boss. “My first week there, they had a companywide meeting, bused us all Downtown to Municipal Auditorium, and I thought I’d gotten myself into a cult. Mr. K comes out on the stage, there’s a standing ovation, women are crying . . .” It didn’t take long for Weir to catch the fever. “He had these three core values up on the wall, even my kids can quote them,” Weir says: Treat others the way you want to be treated, those that produce share in the rewards, and company leadership owes it to each associate to provide clarity on where the company is going. Weir tries to apply some of that same entrepreneurial zeal to his own work at the KU Cancer Center, developing drugs for clinical trials and commercialization. “In my world, biotech, we have to be team players. We’ve got to collaborate to get things done,” he says, drawing on another lesson learned under Kauffman. “We identify partners who share common goals, visions or missions. It’s not about who gets credit or who takes the lead; we’re more focused on outcomes and results.”

Bill Kastner

Engineer, Wichita

“Most engineers,” says Bill Kastner, “hope that what they do will be useful to mankind.” Kastner doesn’t have to worry. The proof of his engineering contribution to the world is probably in your living room right now: If you own a television with a screen bigger than 13 inches, it incorporates the technology Kastner developed to create closed-screen captioning used mainly by the hearing-impaired. “This is the one project which I did which I feel has benefited so many people,” he said.

His work on that system came while he was with Texas Instruments, based on a request from the Public Broadcasting System. “My background was in logic design and I felt confident that I could accomplish the design portion,” Kastner says. “My supercomputer design experience enabled me to complete the project within six months.”

That’s the kind of performance his teachers back at Salina High School (now Salina Central) might have expected back in the mid-1950s, where Kastner earned fifth place in the statewide scholarship exam in physics.

“The care and concern of family and colleagues who encouraged me to become the best I could be is what I think is so characteristic of the people of Kansas who shaped my life,” he says.

Texas Instruments beckoned after he graduated from K-State, and he and his wife came back to Kansas after his retirement, when he took a position at Cessna Aircraft in Wichita, where they still live today.

David Ruf

Engineer, Farmer and Jayhawk, Leawood

Dave Ruf’s 20 years at the helm of Burns & McDonnell, say those who worked closest to him, were defined by a series of four-letter words. Here are two: “Hard” and “work.” They would become hallmarks of Ruf’s leadership in making the engineering giant an employee-owned company in 1985, averting a sale to a German company by parent Armco Steel. That structure, Ruf says, gave everyone “‘skin in the game.’ …

We would now control our own future and not be at the mercy of an out-of-town owner. We would become a family and rise and fall together with our success and failures.” As for the salt content of his vocabulary, Ruf acknowledges, “I was very direct, and sometimes simplistic, in my com-munication. Six-syllable words didn’t do it for me. I wanted everyone to know exactly how I felt. … Then the charge was always … Now let’s get it done!’ ” A proud Jayhawk who appreciates the differences in values that precipitated the real border war, Ruf crosses into Missouri to cite a great source of inspiration: Harry Truman, with his “buck stops here” mentality. “I felt responsible for the well-being of all our employee owners and their families with every decision I made,” he says, which led to “many sleepless nights for me.”

Roger Barta

Smith Center High School

In November 2009, five-time state champion Smith Center High School saw its 79-game winning streak—the longest in the nation at that time—snapped by Centralia in the title game. The reaction? “The kids reacted positively, the town was real supportive,” head coach Roger Barta recalls. “I think everybody thought it was just another game, but one where we just happened to be short on the scoreboard.” That’s it: No bitterness, no moaning. Just back to school, and back to work preparing for the following season. That’s the kind of no-nonsense culture that marks the city and the state, Barta says: “We try to teach our kids to respect everybody—how to work hard, try to make ’em be great citizens and care about each other.” It really isn’t about the wins and the losses, although there have been plenty of the former during his 34 seasons there. Smith Center’s football success even caught the nation’s attention at the height of its streak, when The New York Times produced a front-page profile on the team and town. “I still get e-mails and calls from people out of blue” after they find that story on-line, Barta marvels.

A glossy won-loss record could have earned Barta a higher-profile jobs almost anywhere, but he’s anchored in north-central Kansas. “We had chances to move, but we had kids in school,” he says. “I think Smith Center is a great place to raise kids. I don’t know how we did it, but our kids all turned out pretty well.”

Kent Glasscock

K-State Institute for Commercialization, Manhattan

No matter where Kent Glasscock lands, he isn’t about to forget his roots. “I’ve never lost the belief that if it can be done in the world, a Kansan can do it,” says Glasscock, president of the Kansas State University Institute of Commercialization. “Kansans are defined by a firm belief that America truly is a meritocracy and that talent, character, simplicity of purpose, relentless drive and original thought will always be the pillars upon which rest individual and community success.”

In his role with the institute, Glasscock works in coordination with researchers at K-State, MRIGlobal and Wichita State University to monetize intellectual capability, taking research into the international marketplace in partnership with emerging, national and multi-national companies.

With an enduring entrepreneurial background, Glasscock is also chairman, CEO and majority shareholder of his family business, the Kansas Lumber Homestore. Before joining the institute, he spent 16 years in public office, 12 of them in the Kansas House of Representatives. That service, he says, taught him leadership lessons that could apply to any of life’s endeavors.

“My time in elective office taught me that if one can learn to lead with toughness and integrity in the complex, frustrating public process, then you can avoid being just so much freight on the train of self-governance.”

Vera Bothner

Bothner & Bradley, Wichita

As an expert in strategic communications, Vera Bothner has a rare perspective on the relationship between Kansas values and boardroom duties. “The most successful and visionary Kansas leaders really do embody all the best qualities of Kansas and Kansans,” she says. That often means quiet leaders with even temperaments—but rarely, big egos.

“They can articulate the issues, and also listen, connect, and most have a good—and often self-deprecating—sense of humor.” She’s a partner in Bothner and Bradley, and has worked in for-profit, non-profit and public sectors as both an advertising firm executive and a consultant. What she sees in executive leadership in the state is the advantage that comes from the simple virtue of humility. For most organizations, she says, that typically Kansan quality is “a huge benefit because it does foster a ‘we’re-in-it-together’ attitude. Where it probably hinders us most is when we go to tell the Kansas story outside the state, whether that’s as a business or a community. We often undersell our strongest assets.”

Take, for example, the sprawling Gypsum Hills west of Wichita. To Bothner, “driving from Wichita home to Ashland through the Gyp Hills and into the Red Hills in Clark County” provides instant reconnection with an undervalued asset that helps make Kansas great. “My great-grandparents settled as farmers/ranchers near Sitka,” she says. “To me, it has that quintessential Kansas landscape that’s open, somewhat wild and beautiful.”

Pat George

Secretary of Commerce, Topeka

At age 19—a time when many are still trying to figure out where to live, let alone what to do with their lives—Pat George bought his first home. His business acumen took him into real estate, car dealerships and investment firms, and gave him a graduate degree in business from Hard-Knock U. It also gives him a decidedly business-owner perspective as Secretary of Commerce in Kansas, a role he believes he’s been preparing for all of his life. Part of his economic worldview is framed by his observation that “too much debt is a business killer.” That’s why he’s completely on board with Gov. Sam Brownback’s vision for generating growth, from tax reform to spending controls and greater selectivity in setting spending priorities. “We are moving in the right direction,” George says, “More Kansans are working, a number of companies are expanding and increasing state revenues—but there is a lot more work to do.”

George says he finds strength and direction in those who have gone before him: “There is an area between Meade and Medicine Lodge along Highway 160 in western Kansas that really brings home to me what it means to be a Kansan,” he says. “When I see the landscape and rolling hills of this area, it’s easy for me to imagine what it was like to be an early settler in this region and the challenges that needed to be overcome to make a good life here. Early Kansas settlers overcame a lot of adversity, but they helped pave the way for everything else that has happened in the state.” In his current role, he hopes to leverage the Kansas traits of hard work and working together. “The easier we make it for businesses to operate and succeed in Kansas,” he says, “the more economic activity and job growth we will have.”

Tom Bell

The Salina Journal, Salina

With common sense, independence, self-reliance and boundless curiosity, Tom Bell has successfully led The Salina Journal through some of the most trying times for newspaper journalists. In an era where bigger-city dailies have seen circulation plummet, Bell’s newspapers daily press run of nearly 30,000 is only fractionally lower than it was in the pre-Internet days.

“One must learn to dance much quicker in this environment, which means making crucial decisions with less information and planning. Ready-Fire-Aim is the new reality,” says Bell, the publisher in Salina since 1998.

Even though the importance of newspaper in a traditional print format has been challenged, Bell and his staff have found ways to reinvigorate The Journal’s value by broadening its reader services, including embracing online enterprises such as coupons, social networking, auctions, streaming video, community directories, polling, public forums, Facebook, Twitter and breaking news texts and e-mails.

“My high point is seeing the newsroom staff embrace a 24-hour news cycle and become enthusiastic about online opportunities,” he says.

Taggart Wall

Mayor, Winfield

Nearly five years ago, Taggart Wall sat through a speech at Boys State and heard Ron Thornburg, the secretary of state for Kansas, explode the myth that leadership would one day be passed on to them. “He challenged us to step up and take control of the present and to take those positions from the generation currently in power.” “I guess I took that to heart.”

No kidding: After an unsuccessful run for City Council in his hometown 2007, when he was 18, Wall ran again in 2009, working to earn support one vote at a time with those concerned about his youth. “I usually asked them to judge me on something other than my age,” Wall says. “I was asking them to give me a chance and that I would do my best to listen and learn from others.” He won that seat, and because the position rotates among members, Wall became mayor of Winfield last year, at 22. “My job as mayor is to put forth a compelling vision for Winfield and to rally the people” around that, he says. Example: To keep the city competitive, he advocated for faster debt retirement, which paid off when the Newell Rubbermaid Co. wanted to expand on a site there with a 500,000 square-foot facility and 200 new jobs. “When investment was needed to help make this possible, we were ready to jump; many cities aren’t,” Wall says.

Chuck Magerl

Free State Brewing Co., Lawrence

Nobody who brews beer for a living would compare the fruits of his current zymurgical talents with that first batch of homemade beer, and Chuck Magerl is no exception. Ask him how that one turned out, and he diplomatically notes, “Promising enough to keep me going.” And how: Magerl played a key role in advocating for changes to state beverage laws in the 1980s, paving the way for him to open the state’s first working brewery in nearly a century—Free State Brewing Co. in Lawrence—

in 1989. The first batch of commercial production, Magerl says, “was loud, hot, wet and awesome, and that’s still the way it is today.” Other brewers have followed his lead in cities around Kansas, but Free State’s signature Ad Astra Ale—along with seven other regular varieties—have set a standard of excellence. None of that, however, would have been possible without an aspect of Kansas often used to deride the place: It’s small population. “Our state legislators are still remarkably accessible, and it’s possible to get an idea across in a forum that you would never be privileged to in a populous state like California,” Magerl says. That opportunity, along with his own personal drive, compelled him to push for the relaxed laws on production. “After years of watching the beer scene emerge on the West Coast,” he says, “I didn’t want to let the moment pass by. I couldn’t bear the thought of regretting in later years that I didn’t push to make it happen.”

Andre Butler

Heart to Heart International, Olathe

Andre Butler considers integrity a quintessential characteristic of somebody from Kansas, a “part of the DNA of Kansans and this is something that will never go away.” It’s a trait that comes in handy for the CEO of Heart to Heart International, an Olathe-based humanitarian organization that has worked in more than 100

countries to deliver programs promoting health care, disaster relief and community development. “I’ve learned that when you make integrity a part of your everyday life, everything else follows; success, respect and honor.” Which is exactly what he thinks Kansans are all about: “When you think of Kansas and its residents, you think of people who not only care about one another, but also care about those who visit their state. The people of Kansas are open-minded and treat others with kindness and fairness.” All of that ties in directly with Heart to Heart’s commitment to delivering aid where the need is greatest; the company says 98 cents of every charitable dollar reaches the intended recipients. That makes administrative costs a fraction of the 20 percent generally considered a marker of efficiency in the non-profit sector. “I always say that fundraising and sales are not brother and sister, but they are related,” Butler says. “The one truism is that when you believe in what you are ‘selling’

or the service you’re offering, then your success is not far away.”

Linda Clover

Ball of Twine, Cawker City

She’s been called the Belle of the Ball, and in Cawker City, Kan., that means something special. Linda Clover is the caretaker of the World’s Largest Ball of Sisal Twine, an attraction that has drawn tens of thousands of tourists to town. The ball has made the state the subject of conversation—and, yes, condescension—for decades since Frank Stoeber started gathering string in his barn in 1953. Ill health prompted him to turn the object of local lore over to the city in 1961, and things just sort of took off from there. Today, the ball is made up of 1,444 miles of twine and weighs almost 9 tons. Clover’s role with the ball’s legal owner, the Cawker City Community Club, is to assist just about anybody in adding to this unique venture, whether they’re locals or out-of-towners. And frankly, many of the latter just don’t get it when it comes to the ball. The ball isn’t just twine, she says; it’s a link to the area’s farm heritage [twine used to bale hay] and to those who have made the trip there to add their own strands: “We are who we are because of what has gone before in our lives and others,” Clover says, and the ball, in part, represents that.

Maritza Segarra

8th Judical District , Junction City

The knock on Kansas is that its social conservatism makes it resistant to change. Maritza Segarra will tell you it ain’t necessarily so. Case in point: Susanna Salter of Argonia, who in 1887 became the first woman in the nation to be elected mayor, anywhere. Take that, you East Coast trend-setters. Segarra looks to the Salter saga for inspiration, and relates: In 2007, she became the first Latina district judge in the state of Kansas. “I’m inspired by the history of women in Kansas,” Segarra says,

“and I’m proud to be a small part of that history.” An appointee of former Gov. Kathleen Sebelius, Segarra serves on the 8th Judicial District bench in Junction City.

Her rise through the legal ranks, coming up through the public defender’s office, has given her an opportunity to see a side of the state’s people that doesn’t show up in

eco-devo promotional films, and to advocate on their behalf. Constitutional rights, she says, “belong to all, whether rich or poor,” and she’s a firm believer in the need to fully fund the State Board of Indigent Services. Her path was illuminated by the lessons of an influential small business owner: her father. “He showed me the value of hard work, and doing and being the best you can be,” she says. “He always told us that you should never allow your future to shape you; you must shape your future.”

Greg Smith

Kansas House of Representatives, Overland Park

Both sides of Greg Smith’s family came to Kansas in the 1850s, and some even survived the cross-border raids of William Quantrill. So you can believe him when he says, “I feel it is important to know the past so we can learn from it and be successful in the future.” That means fully appreciating the values of perseverance, integrity, honesty, and a strong sense of doing what is right that marked Kansas back to the earliest days of the state, he says, and the fight against slavery. That historical sense of doing the right thing was a prime motivator in his push for the Kelsey Smith Act, giving police in Kansas greater access to cell-phone records after his daughter was kidnapped and murdered in 2007. Smith and his wife created the Kelsey Smith Foundation, which promotes safety for children and young adults, and his work with lawmakers led him to seek public office himself. In 2010, he defeated an incumbent state representative and returned that seat to the Republican Party for the first time in 14 years. Already, he has declared his intent to move to the other side of the Capitol, the Senate. His goal there? “To ensure Kansas remains a place where people want to raise their children and want to call home.”

Greg Smith

Kansas House of Representatives, Overland Park

Both sides of Greg Smith’s family came to Kansas in the 1850s, and some even survived the cross-border raids of William Quantrill. So you can believe him when he says, “I feel it is important to know the past so we can learn from it and be successful in the future.” That means fully appreciating the values of perseverance, integrity, honesty, and a strong sense of doing what is right that marked Kansas back to the earliest days of the state, he says, and the fight against slavery. That historical sense of doing the right thing was a prime motivator in his push for the Kelsey Smith Act, giving police in Kansas greater access to cell-phone records after his daughter was kidnapped and murdered in 2007. Smith and his wife created the Kelsey Smith Foundation, which promotes safety for children and young adults, and his work with lawmakers led him to seek public office himself. In 2010, he defeated an incumbent state representative and returned that seat to the Republican Party for the first time in 14 years. Already, he has declared his intent to move to the other side of the Capitol, the Senate. His goal there? “To ensure Kansas remains a place where people want to raise their children and want to call home.”

Ryan Hanna

Kansas Buffalo Association, Longton

Ryan Hanna admits it: He’s always been fascinated with bison. “When you have the pleasure of raising bison, there is no better way to connect with the land and yourself than to sit in a prairie grass pasture in the middle of a herd of bison”—in the pick-up truck, of course. So says Hanna, now president of the Kansas Buffalo Association. “They are very humbling animals and can really make you take things a little slower.” They also are interesting in dichotomy: Despite being better lower in fat than beef, pork or chicken, only 40,000 go to slaughter every year, while 125,000 cattle are sent to market every day in the U.S. Hanna is working to change that imbalance, both on the ranch and with the association.

From a young age, he has understood the importance of family and heritage—two characteristics he believes help define what it means to be a Kansans and he said hold to be true especially for to agriculture-based families, like his. “Agriculture has always been a way of life for us,” he says. “My childhood was spent travel-ing all over the country with parents, who were professional rodeo competitors.”

David Basse

Musician, Leawood

When he was 11 years old, David Basse begged his mother for drum lessons and got them. Let’s hope she liked the sound, because it would fill the home in Norfolk., Neb., until the day he left home. Throughout that span, and the 20 years that followed, Basse was on those drums four to eight hours a day; “love” isn’t strong enough a word to describe what he’d found. “I distinctly remember coming out of the first lesson, getting in the car and declaring, ‘I have found my life’s work,’ ” he says. He added singing to his repertoire at 17, developing a signature style that has been called a blend of Mel Torme, Jon Hendricks and Al Jarreau. Basse has firmly set his place on the Kansas City jazz scene, and has taken that sound to stages around the planet. “Kansas City,” he says, “is where jazz and blues meet. As such, musicians come from all around the world to experience what we who call Kansas City home sometimes take for granted: Eating the best barbecue, jamming the blues all night, and, as Calvin Trillin once said, the Sirens of Titan got nothing on the Strumpets from St. Joe and Topeka. His favorite venue? “The Folly Theatre is the finest hall in the Midwest,” Basse says. “Many compare its acoustics to those of Carnegie Hall. I love the Folly’s piano and the way that each of the 1,100 seats seems like the best seat in the house.”

Scott Van Allen

Kansas Wheat Commission, Clearwater

Ripe wheat fields in June mean one thing to Scott Van Allen: home. A master wheat farmer in the wheat-growing cap-ital of the Wheat State, he champions that

livelihood as a member of the Kansas Wheat Commission. Successful wheat farmers, he says, exhibit two key traits you find in almost any Kansan: “Belief in a power much greater than yourself and a solid honest work ethic.” After all, “a strong belief in the power of Mother Nature is essential on any farm,” he says. “Growing up on a farm and learning that all the planning and hard work you put into a crop will not guarantee a return—a hail storm can wipe out a year’s work and investment in a few minutes—was a great teacher. You must work with, and not against, that power.” His father farmed the same piece of ground near Clearwater in south-central Kansas. And location, as it turns out, is as important in wheat growing as it is in real estate. “Sumner County enjoys the best of both worlds,” says Van Allen, sitting between the Flint and Red Hills—ample rainfall and fertile ground. Weather soil nutrition, fertilizer choices and seed-variety selection play parts, he says, as do skills in judging herbicides or insecticides use. Farmers in the county have learned the benefits of diversifying their crops, Van Allen says, “but we are still the ‘Wheat Capital’ and I am very proud to represent us” on the commission.

Chris Walker

Emporia Gazette, Emporia

Sometimes, growing up in the family business means walking in the footsteps of giants. So it is with Chris Walker, fourth-generation publisher of The Emporia Gazette. The newspaper was the launch pad to national fame for the legendary William Allen White—Walker’s great-grandfather. Walker was born more than a generation after White’s death in 1944, but carries on the tradition that gave us the Pulitzer Prize-winner known as “The Sage of Emporia.” “The things he wrote about then are so relevant today,” Walker says. “We like to think these times are completely different, but when you look back in Kansas history, you realize we’ve been through this before. His writing transcended time.”

Walker inherited what he calls “an excellent road-map” for success. “You look at journalism today, the buzzword is ‘local.’ That’s what he did,” Walker

says.“He wanted 100 local names on the front page, and believed if you put names in the paper, people would read.”

Walker burnishes that legacy with his own polish in overseeing The Gazette. “It’s not just the names that are important,” he says, “it’s the telling of

stories about what people are doing and documenting daily life.”

John Hadl

The University of Kansas Athletics Department, Lawrence

John Hadl has left a big footprint on Kansas; you can tell it’s his because of all the cleat marks. Hadl was born in Lawrence and stuck around to make football history—embracing the concept of all-around excellence—by playing offense, defense and special teams for the University of Kansas.

He launched his collegiate career by leading the nation in punting in 1959. He still holds school records for the longest interception return, taking one 98 yards for a score against Texas Christian, and longest punt return, for his 94-yarder against Oklahoma. Hadl went on to become the first Jayhawk to earn All-America honors twice

(as a halfback in 1960 and a as quarterback in 1961), and was elected to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1994. His jersey, No. 21, is one of only three retired at KU.

Hadl then played 16 years in the NFL—for the San Diego Chargers, the Los Angeles Rams, the Green Bay Packers and the Houston Oilers. He was elected NFL Man of the Year in 1972. After his playing career, he was head coach for the Los Angeles Express and an assistant coach for his alma mater.

Still in Lawrence today, Hadl is currently the associate athletics director of major gifts, a position he has held since 1992.

Steve Cadue

Kickapoo Indian Nation, Horton

The very face of the Kickapoo Indian Nation in Kansas might well be Steve Cadue’s: This past fall, for the 12th time in 30 years, Cadue has been elected chairman of the Kickapoo Tribe in Horton, and he has held every elected leadership position within the Kansas tribe.

Cadue has been active in the media and political realms, advocating on behalf of Indian tribes’ sovereign rights to operate gaming facilities in Kansas. And he’s been vocal about the Kickapoo tribe’s goals and needs for its reservation.

“Federal Indian policy is at the cornerstone of the foundation of the United States of American,” Cadue has said. “Indian gaming is an Indian initiative. Indian gaming is not a happenstance. [It] began with a need for a better tribal economy and a strong belief in Indian sovereign rights.”

Additionally, Cadue has been influential on the big screen—producing “Law of the Land,” a documentary miniseries focusing on the history of Indian gaming and Indian Self-Determination. Cadue and many members of the Kickapoo tribe also participated in the “The Only Good Indians,” a movie that featured the Kickapoo language and culture.

Bob Redford

Walnut Valley Association, Winfield

Perseverance, says Bob Redford, is what defines someone from Kansas. At least it defines Bob Redford. How else to explain, on his watch, the evolution of a community music festival into a nationally known bluegrass competition, one that draws as many as 16,000 people to Winfield for four days every September?

“Most of the time, with perseverance, jobs can be accomplished that were previously thought to be impossible,” Redford says. Forty years ago, he was asked to help finance an event ambitiously titled the “National Flat-Picking Championship and Walnut Valley Bluegrass Festival.” Today, bluegrass fans simply know it as “Winfield.” He’s been president of the organizing Walnut Valley Association since its launch, helping build it into what the International Bluegrass Music Association once dubbed the “Bluegrass Event of the Year.” Along with dozens of concerts each year, the festival has grown to include national and international championships for masters of the banjo, mandolin, hammer dulcimer and more. Perhaps the greatest tribute to Redford’s work came from John McCutcheon, a folk-music legend who said the festival had “made a small town in southeastern Kansas a hub of the acoustic music world. It’s made great music, great friendships, and more than a few babies.”

Donna Pichler

Pichler’s Chicken Annie, Pittsburg

By Donna Pichler’s conservative reckoning, perhaps 2 million chickens have gone to that Great Henhouse in the Sky over the 70 years since Annie Pichler opened Chicken Annie’s in 1933. Back then, she was trying to feed a family facing destitution after her husband was maimed in a coal-mining accident. As it turns out, she launched a cottage industry in Pittsburg. A few years later, Joe and Mary Zerngast opened Chicken Mary’s, and a fry war was on to determine the best fried chicken in southeast Kansas.

For years, those establishments were to chicken what Delmonico’s was to steak, and to family ties what the Hatfields were to the McCoys. But Pittsburg is, comparatively, a small town; as it happens, the Pichler’s grandson Anthony and the Zerngast’s granddaughter Donna dialed back the competitive factor by getting married. The two operations continue today, and still draw food-programming TV crews to town, some for the Romeo and Juliet factor, but mostly for the chicken.

Just don’t try getting the recipes out of Donna Pichler. She will, however, part with some advice: “We’ve been asked several times what the reason for our success is,” she says. “We have found some people tend to use low-quality ingredients, improper preparation and over-frying.” Fix those, and the rest usually takes care of itself.

Her work, though, is about more than making a living. “This restaurant is one of my most valued assets because it involves my past, my present and my future family,” she says. Nearly abutting the Missouri state line, Pittsburg is closer to the Ozarks than to the plains that dominate the state, and Pichler says southeast Kansas “is a wonderful retreat for me,” a place that is at once “inspirational, traditional, and family-oriented, with spectacular core values and beliefs.”

Stacy Barnes

The Big Well, Greensburg

Faith. Family. Hard work. They are hallmarks of Kansans in general, says Stacy Barnes, and of Greensburg residents in particular. She’s seen the power of those hallmarks since that date in May 2007, when a savage tornado leveled most of the town. Among the buildings demolished in that storm was the ground-level headquarters of the Big Well, Greensburg’s pre-tornado claim to fame. That roadside attraction, built around an unprecedented pioneer engineering effort in 1887, has for 125 years maintained its claim to being the World’s Largest Hand-Dug Well.

Like the rest of the town, that bit of local folklore is coming back to life. Barnes’ charge as director of the well is to help facilitate the $3 million construction project—managed by McCownGordon Construction of Kansas City—that will yield a modern museum at the well site later this year. She’s the city’s Tourism Director, but also president of the board of directors for the private, not-for-profit 5.4.7 Arts Center, which draws its name from the date of Greensburg’s meteorological infamy.

“We had a great opportunity for an amazing facility, and jumped in with both feet,” she says, providing a town that had been physically ripped apart a therapeutic treatment that was desperately needed.

Jim Sharp

World War II Veteran, Manhattan

In a time when thousands of World War II veterans die each day, hundreds of 21-gun salutes are fired and “Taps” rings out, decorated veteran Jim Sharp thinks back to days far removed from Kansas. Serving as combat soldier during Battle of the Bulge in World War II, then as a sergeant of the guard during the Nuremburg War Crimes Trials, Sharp admits his wartime experiences, witnessing “death and destruction all around,” had made him a better person.

“Having seen man’s inhumanity to man, first hand, I am more tolerant and sympathetic to all human beings and do not get antagonistic because someone does not agree with me,” he says. “War or violence, killing each other, will not solve our problems; it just compounds them.”

Sharp has authored three books; in his most recent, Sgt. of the Guard at Nuremberg, he writes about his experiences as a select guard at Nuremberg over the 22 Nazi defendants from Adolf Hitler’s cabinet. “I was in contact with the defendants on a daily basis,” he says, “and secured the autographs of Herman Goering and nine other defendants.”

After his time spent in the military, Sharp returned to Kansas and studied business at Kansas State University and spent most of his career at the Kansas Farm Bureau, working in information systems. Sharp’s two other published books are Black Settlers on the Kaw Indian Reservation (2008) and Diary of a Combat Infantryman (2010).

Aaron McKee

Purple Wave, Manhattan

Aaron McKee says the spirit of Kansas is grounded in entrepreneurship, and when you combine that with 82,000 square miles of space, “there are lots of places for enterprising Kansans can start a business without too much interference.” The difficulty facing start-up companies, he says, is that the state isn’t brimming with the same kinds of resources that get fledgling companies to the next level.

His own experience in that a case in point: More than a decade ago, he launched his own company specializing in auctions of farm equipment. In 2009, Purple Wave

eventually morphed into an on-line auction site for farm vehicles and equipment. It took a fair amount of work for his Manhattan-based business to become an “overnight success” but his company made the 2010 Inc. Magazine list of the nation’s 500 fastest-growing private companies in 2010. The site boasts 80,000 registered users and 140,00 monthly visitors.

That success is testament to the bedrock values you find throughout the state, says this father of five: “Growing up on a farm in rural Kansas, where people really had to do most things for themselves, has helped me to have the confidence to face challenges head-on.”